Candor: A Simple and Powerful CI Ecosystem

Candor is a CI ecosystem - a dashboard with runners - that not only caters to my needs but is also a manifestation of what happens when I let my passion and perfectionism get the better of me. Behind it is a multi-year process, months of active development, fuelled by caffeine and sheer commitment. If you would like to check it out, you can view the project on GitHub.

With this post, I intend to highlight not only the technical details but also the process. This is a story of passion, ignorance, and perseverance. At the point of writing, I would consider Candor to be my magnum opus, but we shall see how well this ages.

This post has a lot of thoughts and ramblings. Feel free to skip to whatever topics interest you!

Table of contents:

- Humble beginnings

- What’s the plan?

- Phase 1: A runner

- Phase 2: Containers

- Phase 3: A dashboard

- Phase 4: Constraints and parameters

- Phase 5: Usability and quality of life

- Phase 6: Distributing

- No free lunch

- Final remarks

Humble beginnings#

The story of Candor begins sometime between 2018 and 2020. I wanted continuous integration and deployment for a project, and coming from the Java ecosystem, I ended up with Jenkins.

Jenkins#

Jenkins isn’t necessarily a terrible tool, but in my experience, it does come with substantial headaches. While incredibly powerful, it’s also hard to set up. I spent a great amount of time tweaking the pipelines and reading blog posts to achieve exactly what I wanted.

I’m a big fan of minimalism, and I feel within the context of CI/CD this does make your life easier. Jenkins does so much and has so many complex features, I felt overwhelmed by both the user interface (which I had to theme to make it look less 2010) and also its feature set. I said to myself: I wish there was a simpler way to do all of this without the bloat.

A first attempt#

I rose to the challenge of building a simple CI/CD server. When eliciting my requirements, I realized that my CI server would actually be super simple. I could use a simple REST application that would:

- Expose an endpoint for a pipeline that would act as a trigger.

- When invoked, run the pipeline according to some sort of action sequence.

- Provide some CRUD endpoints to manipulate a pipeline’s action sequence (and possibly other metadata).

With that, I set out to start coding. I wanted to learn Rust, so I picked out Rust, a nice web framework, and was ready to start. Unfortunately, the project never manifested itself…

GitLab, GitHub, Drone, et al.#

It’s the 2020s, and for work and university, I am using GitLab. I think GitLab’s really developed my interest in continuous integration. It made me realize that CI does not have to be painful like in Jenkins, rather I can use YAML to elegantly define a few steps and that’s it! From then on, I knew exactly what I wanted, I just had to find it.

As a person, I use GitHub with no intention to migrate to GitLab, so unfortunately I cannot use their CI. My friends were using various third-party providers such as CircleCI. These are great for the industry, but I wanted freedom. Will I ever use up 2000 CI minutes a month? Unlikely. But, I want to host my own infrastructure and feel completely free and limitless, and these providers were not cutting it.

At this point, GitHub Actions is gaining a lot of traction. While I prefer GitLab’s CI, Actions was a really strong contender but ultimately had one pitfall: private repository minute limits. The solution to this would be self-hosted runners, but with security concerns I ended up deciding against it.

I talked to a friend about my conundrum, and he suggested Drone. Indeed, Drone had everything I was looking for. On top of that, it was sleek, minimal, and seemed to “just work”. I installed it on my server, eager to use it, and was prompted to register and agree to their privacy policy, even though it was hosted on my machine. So close, yet so far: I no longer felt in control, and hence discarded it.

What’s the plan?#

It was clear to me what I had to do. Unless I wanted compromises, I had to build my own CI ecosystem. But what should this actually do? Decided that my definition of done would be being able to use Candor in production to replace my existing Jenkins pipelines. Concretely:

- Pushes to the main branch of a GitHub (or any other provider with webhooks) repository should trigger a build.

- The build process takes the following steps:

- The repository is cloned.

mvn clean packageis run to build a.jarfile.- The

.jarfile is archived such that it can be downloaded from the web.

- Once this completes, a deploy script on my server is run. I admit that the last part is part of continuous delivery, but such a deployment is trivial if the runner can quickly SSH into a server and run a script.

Overall, the following rough requirements were elicited:

- Everything should be minimalistic, but not at the expense of usability. Common tasks should be easy to do, less-frequent ones may be abstracted away.

- Pipelines are human-friendly to define and run Docker images as stages.

Phase 1: A runner#

The first point was clear: a runner that can run arbitrary pipelines. The most important feature of the runner should be that it is as simple as possible. No abstraction pitfall, no more features than are strictly necessary. In fact, a runner could just be a single endpoint.

I decided on TypeScript, with Express.js as the server. It’s nice and high-level, so I could focus on the business logic and always fall back to one of the NPM packages if I needed to. And of course, I’m a big fan of static typing.

Oftentimes, pipelines create some sort of artifacts. I did not want to bother with artifact management - this should not be the responsibility of the runner. Therefore, I decided to provide the option to archive any files to S3.

The runner is dead simple.

You send a request to /run with a bearer token and a JSON payload.

This payload is the pipeline plan, a description of what the runner should do.

An example pipeline that clones a repository and builds it looks like this:

{

"plan": {

"stages": [

{

"name": "Checkout",

"image": "alpine/git",

"script": [

"git clone https://github.com/ib-ai/IB.ai /home/work"

]

},

{

"name": "Compile",

"image": "maven",

"script": [

"mvn clean package -Dcheckstyle.skip"

]

}

]

}

}

Phase 2: Containers#

If you paid attention to the previous snippet, you’d have noticed that I can provide an image.

I wanted total isolation for my pipelines, so it was quite clear from the start that I would be heavily relying on Docker containerization.

This would sandbox pipelines (to some extent), and solve another issue: security.

At the same time, I wanted the CI itself to preferably run in a container, so I can quickly install it and isolate all of its dependencies.

Unfortunately, arbitrarily nested containers aren’t necessarily something easy.

Thus, I had the following options:

- Run the CI natively, and spin up containers for the pipelines.

- Run the CI in Docker, and somehow containerize further for pipelines if possible.

- Run the CI in Docker, and spin up containers at the host level for pipelines.

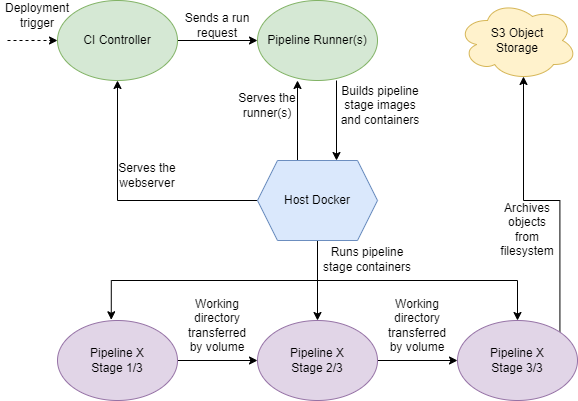

I opted for number 3 as this seemed to be the best compromise, though it did not come without its own considerations. For one, communication between the host and CI needs to be established, effectively giving the CI root permissions. I had to pay extra attention to security. Furthermore, pipelines can now run in containers - but what happens if a pipeline tries to build a Docker container?

After quite some research, I discovered sysbox.

I could then allow the pipelines to specify different runtimes.

By default, it would use runc.

But if one wanted to, for example, build a Docker image, they could use dind with the sysbox runtime.

Phase 3: A dashboard#

At this point, I had a fully working runner, that could in theory be used directly as a CI. However, I wanted Candor to support multiple runners, and also be accessible by a web frontend. Therefore, I derived a simple dashboard.

Requirements#

Requirement engineering is difficult enough on its own, but even more so when you have a product with near-infinite possibilities and lots of ideas. I derived a near-bare minimum based on the Pareto principle: if I can use the dashboard 80% of the time without being inconvenienced, I’d be happy. The 20% are nitpicky but would take up a lot of development time.

In the end, I derived the following requirements:

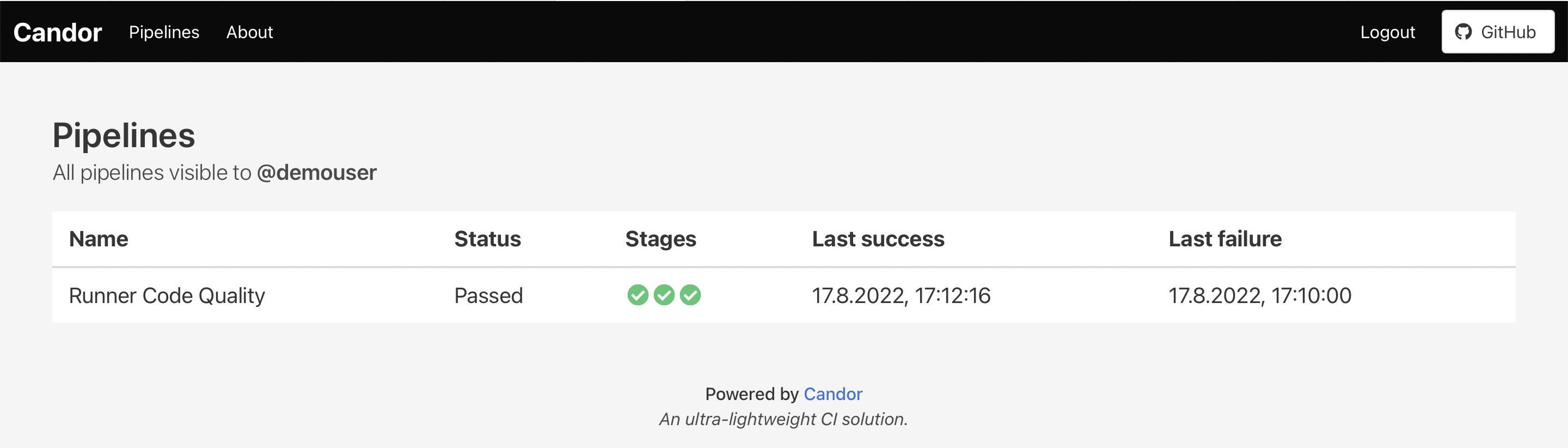

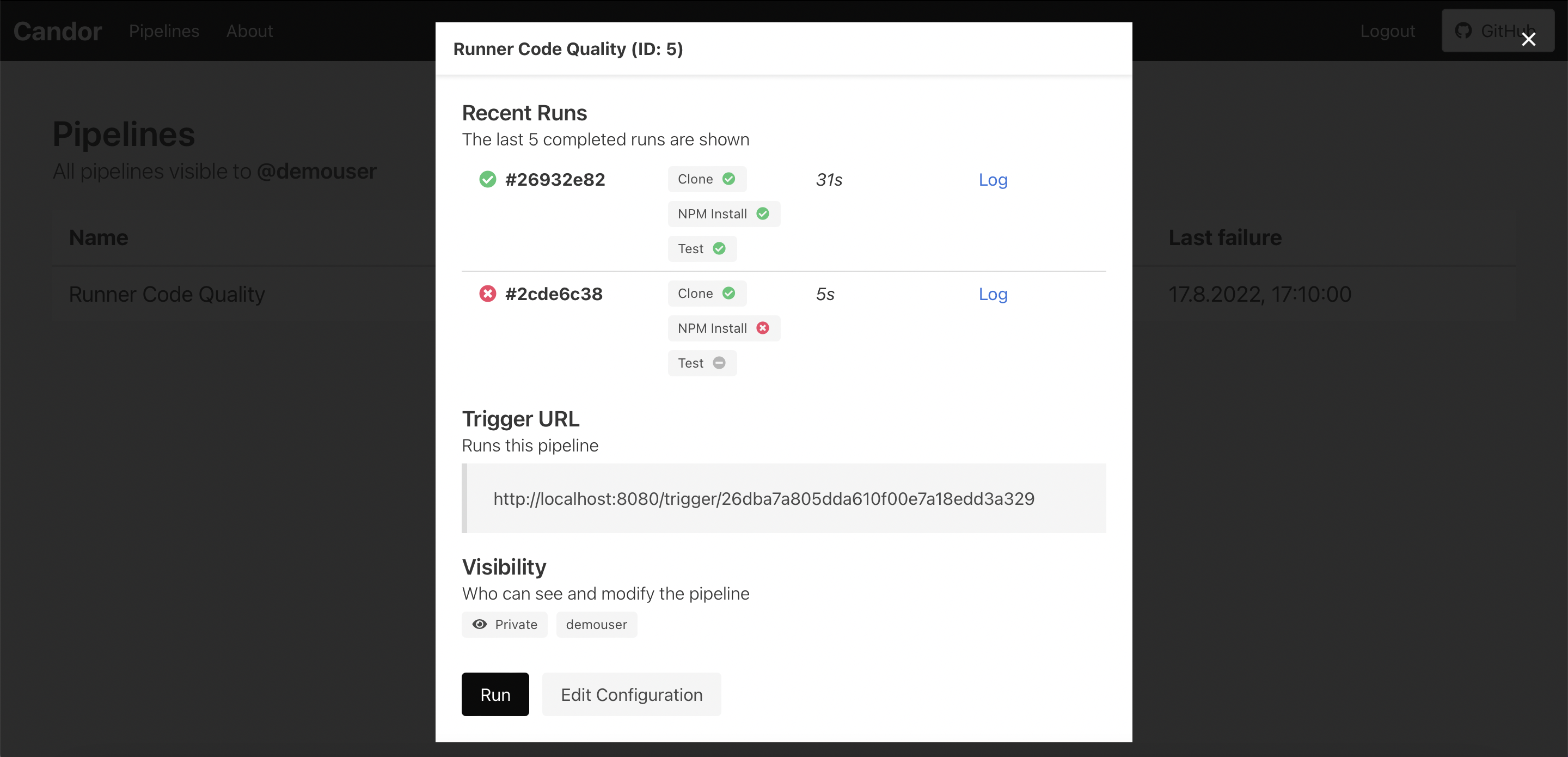

- The dashboard should have pipeline runners, pipelines, and users who can interact with pipelines.

- Runners, pipelines, and users should be managed in a CRUD fashion. Common operations should be done through the web, for example updating pipelines, checking their logs, downloading artifacts, etc.

- Pipelines themselves are defined in JSON, in a similar format to that of runner pipeline plans.

- The dashboard maintains a single truth. When a pipeline should be run, it should figure out what needs to be done and pass this on to the respective runner.

- There should be a list of pipelines and their statuses, as well as the ability to inspect a specific pipeline or pipeline run further.

- There should be basic security. Pipelines should be set to private and require authorization to see run.

The backend#

Again I chose TypeScript with Express.js. I didn’t need anything fancy and I did not want to over-engineer the backend, so I decided to keep it simple. And of course, it would be kept consistent with the runners.

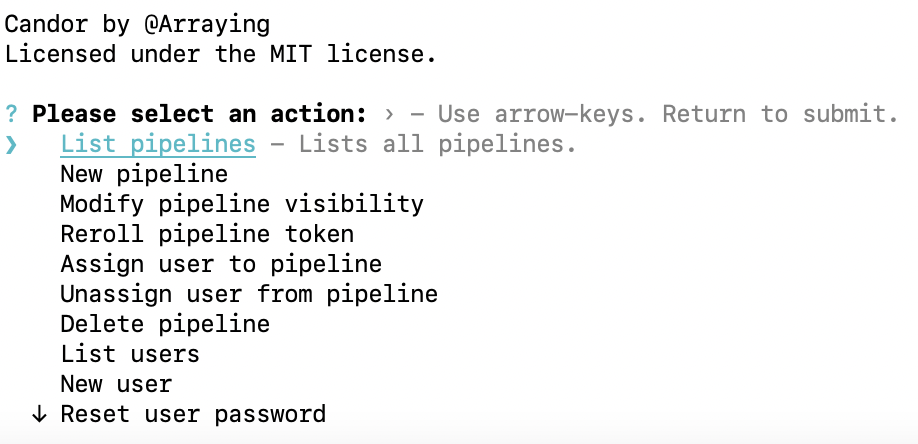

At first, I was considering making a full CRUD panel and using some sort of MVC framework to do all the heavy lifting.

But I thought for an MVP this was a tad overkill, and opted to have the CRUD done mostly through the command line.

Initially, I had a custom CLI.

I moved over to prompts, because it had a batteries-included version of everything I needed, and looked good in

the process.

The frontend#

For the frontend, I decided on a SPA Svelte with Bulma CSS. I found Svelte to be a contender because I was designing a lightweight product and Svelte is (in comparison to React/Vue) super lightweight. I went with Bulma over Tailwind because I wanted to rapidly prototype, and Bulma is beautiful enough out of the box. There was quite a lot of personal preference in this choice; I had been meaning to learn Svelte, and I love using Bulma (as opposed to, e.g., Bootstrap).

I actually decided against TypeScript for my frontend logic (not that there is much of it). Using TypeScript introduces a certain amount of overhead, and I was perfectly content with using JavaScript for the little frontend logic that I had. I may reconsider if I extend the frontend, but in retrospect, I do not regret this choice.

Networking#

One of the biggest challenges of the dashboard is communication between the backend and frontend.

I decided to create a simple REST API (using fetch) that the frontend would consume, either on demand or by polling at short intervals.

This proved to be more annoying and time intensive than anticipated.

I wanted to ensure that the API only exposes exactly what is necessary, in a format that is convenient for the frontend, so there is quite a bit of

business logic in the API itself - it does not just serve a database.

Another aspect of SPA communication is security. I spent quite some time looking into CORS policies and other security best practices. While I did not get around to implementing CSRF, I am quite happy to be using modern MDN practices.

Controlling runners and pipelines#

Since the dashboard is in charge of scheduling, I needed to write a bit of infrastructure code. The dashboard already knows what a pipeline does, it merely needs to find a runner and tell what to do.

Lastly, there still needed to exist some outwards-facing endpoints. For example, an endpoint triggers a certain pipeline. Thankfully, since I had built an API already, implementing these endpoints was really quick and easy.

Phase 4: Constraints and parameters#

At this point, I had a dashboard that could be interacted with and run a set of tasks on demand.

That’s great, but there are still some considerations to take into account when running pipelines.

For example, should the pipeline run on every push, or only when there is a push to main?

Which branch of the project should be built?

Are there any specific variables, such as tags, that the pipeline needs to be aware of?

I wanted a way to be able to extract information from a pipeline trigger and to be able to use this information to make decisions.

By using JSPath, I found a really flexible solution to extract data from an incoming request body.

Constraints#

There are two ways you can constrain a pipeline’s trigger:

- By ensuring one or more headers is/are present and is/are equal to a certain value.

- By ensuring a field in the body of the request is equal to a certain value.

The former is quite easy to implement, but the latter is where JSPath really shines bright.

It provided an extremely elegant solution to extract fields from arbitrarily formatted JSON payloads and compare these values.

For example, by saying that ".foo.bar" should equal ["baz"], our pipeline would be triggered with this body:

{

"foo": {

"bar": "baz"

}

}

This body would not trigger the pipeline:

{

"foo": "bar",

"cow": "moo"

}

Parameters#

Parameters are like placeholders and can be used in virtually every field of the pipeline configuration. The idea of parameters is to provide metadata for a specific pipeline run. This could be, for example, the name of the tag created in GitHub, which can then be compiled into an application when building it in the pipeline.

I decided to let parameters be extracted from three sources:

- Querystrings of the endpoint when the pipeline is triggered.

- The body of the request to the endpoint when the pipeline is triggered.

- A prompt when running the pipeline manually.

Phase 5: Usability and quality of life#

At this point, everything was pretty good. I had a very minimal viable product, though it wasn’t necessarily amazing to use. I decided to take a shot at some small things to improve usability.

YAML#

While JSON is great, I find it much easier and faster as a human to write YAML. I decided that I wanted the user-facing configuration (read: the pipeline plan editor) to be YAML to reap the benefits of YAML. Fortunately, it’s quite easy to convert between these formats using third-party libraries. It’s difficult making (or better yet, reusing) a good web editor, this is definitely a point for future consideration. In the end, I found myself having a much better experience with YAML than with JSON.

SSH#

I wanted a way to be able to, for example, SSH into other servers such that I could use pipelines for CD as well. I opted to create a read-only directory that is mounted during pipeline runs where one could store persistent files that are required for the pipeline to function. Of course, it may be a security issue for one pipeline to have access to a key meant for another pipeline, but for personal use this is fine.

Documentation#

I admit, I’m not the best with documentation. While I’m probably going to be the only one using Candor, I wanted to have good documentation. There are many good reasons for documentation, but my main drive was that I didn’t want to memorize the intricacies of Candor.

I wrote a lot of documentation in the code. This should help me get into the project once I revisit it, and if someone else wants to contribute, it’ll make their life easier. The best of the documentation is the extensive wiki. This is the first time I’ve put so much effort into a wiki, and I think it was a great decision to invest so much time into it.

Testing#

Testing can be fun. In the case of Candor, it wasn’t the best or worst experience, though I found it to be the most tedious part of the project. I generally try to write code in a testable way, though I encountered many situations where I had to refactor my code to optimize it for testability, oops.

I ended up using jest to write my tests.

Mocking imports turned out to be more difficult than expected.

I can highly recommend this blog post, it helped me get started.

Phase 6: Distributing#

This is the final architecture, excluding the database:

That’s a lot of components. How do you effectively bundle these to make Candor easy to install? How can you retain maximum flexibility? Do I bundle the database or not? How can the user configure their setup? Those were some of the trickiest questions I asked myself, and I’m not sure I’ve fully answered them.

I decided against using docker compose to wrap the ecosystem for two reasons:

- The dashboard is a CLI, and attaching/detaching is everything but seamless with Compose.

- Everyone is different, I don’t want to provide a bundle with X, Y, and Z and force the user to make their own if they want to deviate from that. Or even worse, have to maintain them myself.

The biggest choice I made was not to bundle the database with the dashboard. Right off the bat, I did not want to merge and maintain a PostgreSQL and TypeScript image. But beyond that, this removes a level of flexibility from the user. Maybe they want their database stored on a separate server, or they prefer a bare-metal database.

In the end, I ended up with a lot of Docker images, and good documentation explaining how to run and link the services. I’m not fully happy with this, as, for example, updating is difficult. Therefore, I am considering creating some sort of wrapper for installation and updates, but this seems a bit overkill.

No free lunch#

I think I’ve made it clear by now how many small decisions were involved in this project. Virtually every decision has had its trade-offs. I’m not unfamiliar with trade-offs, but I found a CI ecosystem to be particularly unforgiving.

Furthermore, I’ve come to realize how many of the smaller trade-offs are subjective. I could have just as well used Next.js with React for the dashboard and Go for the runner. There are good, objective reasons to use one framework or another, but I was surprised by how little they influenced the end result.

I think the key question to always ask is: “What are my goals and how can I achieve them?” For me, my goal was to make a minimal CI ecosystem that worked for me and didn’t try to be a people-pleaser. I think the decisions I made are sensible and reflect that. That being said, I’m happy to hear your thoughts. What would you have done differently?

Final remarks#

I hope this post inspires you to follow your dreams and take a shot at that crazy pet project. (Send me a link once you’re done!) Even if you don’t end up using it, or it’s not very good in the end, you grow so much in the process. Personally, I ended up with a hyper-focused project that might just fit my needs, for now.

In the end, I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn all the things I did. I’m also super happy with the end product, it ended up much better than I anticipated. There may be so much room for improvement, but in retrospect, I’m really proud of myself and what I created.

I think for me the most important takeaways from this project are that:

- I should not underestimate the dizzying amount of small things required to make even a small project.

- Every decision, no matter how small, has consequences later on in the project.

- There are an insane amount of trade-offs in a CI ecosystem.

- It does not make sense to design a general-purpose system, as chances are it’s either overengineered bloatware or straight-up useless. In my opinion, and in this context, convention severely outweighs configuration.